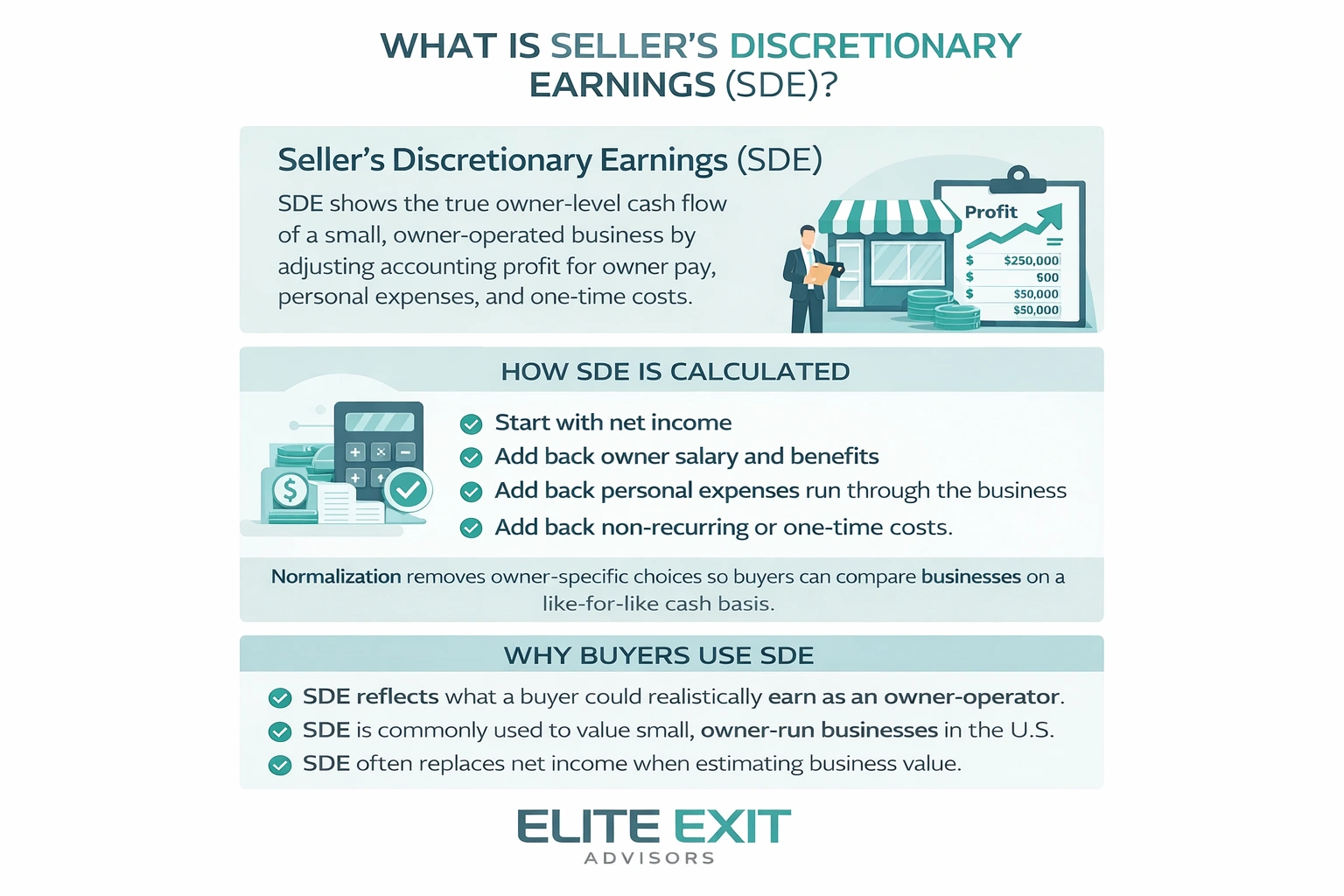

Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) business valuation measures the real cash-earning power of a small, owner-operated company and adjusts reported profits to include owner pay, personal perks, and one-off costs that won’t recur under a new owner. In practice, SDE starts with net income and adds back owner compensation, discretionary and non-recurring expenses, interest, depreciation, and amortization to show what a buyer could reasonably take home as an owner-operator rather than what traditional accounting profit reports.

For Main Street businesses, with most annual revenues under $2 million, the market uses multiples of SDE to estimate value. Across industry data, earnings multiples typically fall between roughly 2× and 3.3× SDE, with the median small business sale price around $337,750 in recent years.

Because SDE reflects normalized cash that’s transferable to a new owner, it’s the dominant valuation metric in U.S. small business sales, helping buyers compare opportunities on an apples-to-apples cash-flow basis and helping sellers justify asking prices before deeper diligence begins.

At its core, seller’s discretionary earnings show what an owner actually earns from a small company once personal items and one-offs are removed. This metric normalizes results so buyers can compare owner-run firms on a like-for-like cash basis.

Normalization adjusts recorded profit and adds back owner salary differences, personal expenses run through the books, and one-time costs that won’t recur after a sale. These categories typically include:

This approach suits owner-involved local service firms, small retail shops, and other owner-operated operations. High owner involvement means net accounting profit can understate the real owner benefit.

Net income often looks low because owners deduct discretionary expenses or pay themselves unevenly. Seller’s discretionary earnings reveal the underlying cash available to an owner and act as the earnings base buyers use when estimating enterprise value for smaller transactions.

When evaluating a sale, buyers want a clear read on real cash that will reach the owner.

Buyers look for a reliable view of ongoing cash flow, not figures skewed by how the current owner pays themselves or runs personal expenses through the company.

Seller discretionary earnings strip out owner-specific financial choices to show what a buyer can realistically take home. That reframes the conversation from accounting profit to owner benefit, which is often how small-business buyers underwrite a deal.

This method is most common for owner-operated companies where ownership and daily management are tightly linked. Buyers who plan to step into the operator role rely on discretionary earnings to model post-closing cash.

It is particularly useful when financials include owner perks, discretionary spending, or one-off items that make standard metrics hard to compare. To be credible, sellers must document add-backs clearly and show a consistent story across statements and tax returns.

A practical starting point for price discussions is multiplying owner-adjusted earnings by a market multiple. This simple rule gives buyers a quick estimate of value while reminding sellers that the number is a starting point, not the final price.

Value = SDE × Multiplier expresses the shortcut clearly. Use it to compare offers and set expectations before deeper due diligence.

Multiples commonly fall between 1 and 4. Lower multiples usually reflect higher risk, weak growth, or heavy owner dependence. Higher multiples suggest strong cash durability, low customer concentration, and easy ownership transfer.

Normalized earnings strip out owner pay and personal perks. That removes noise from financing choices and lifestyle spending.

This makes offers easier to compare across the same industry and helps buyers focus on true operational performance.

To recreate owner-level income, work up from EBT and systematically add back non-operating items.

The standard formula is simple to follow: SDE = EBT + interest expense + depreciation + amortization + owner’s normalized salary + non-recurring expenses + discretionary expenses. Start at earnings before taxes and pull each line from the profit-and-loss statement so the math can be audited.

Interest gets added back because it reflects financing choices a buyer may change. Treat it separately to isolate operating performance.

Depreciation and amortization are non-cash charges. Add them back, but note non-cash items can still matter for asset-heavy firms or future capital needs.

Owner compensation should be normalized. Replace current owner salary, payroll taxes, and benefits with a market-rate amount. This makes the number defensible to buyers and aligns seller expectations.

Draw a clear line between discretionary expenses (personal travel, owner perks, personal vehicle costs) and legitimate operating costs that must remain to run the firm. Only true non-operating items should be added back.

Common non-recurring add-backs include one-time legal fees, unusual consulting projects, and temporary relocation costs. Provide receipts and a concise explanation for each item added back.

For multiple owners, add back all owner compensation, then deduct the market cost of any replacement manager roles a buyer must hire. This yields a realistic post-sale cash figure.

Start with a short worked example to see how each line item boosts owner-level cash.

Normalizing salary makes earnings comparable across owners who overpay or underpay themselves. This improves transparency for a buyer and clarifies replacement cost if a new operator steps in.

Arithmetic (clearly labeled):

Total = $200,000 + 20,000 + 10,000 + 5,000 + 40,000 + 15,000 + 10,000 = $340,000.

Buyers view this figure as an estimate of pre-tax owner cash. They use it to size debt, set expected owner salary after closing, and assess risk. During diligence they will verify add-backs; unsupported items often get removed and can reduce perceived business value.

A correct multiple reflects how buyers value similar firms right now, not a fixed rule you can apply universally. Market demand, recent sales, and buyer appetite move multiples even when SDE stays unchanged.

Industry momentum matters. Fast-growing sectors or high buyer interest lift multiples across comparable companies. Track recent sales and use them as anchors for pricing.

Recurring revenue, long contracts, and high retention support higher earnings and value. Project-based or one-off sales weaken the case for a premium multiple.

High customer concentration, supplier dependence, or volatile sales push multiples down. Stable, diversified income streams increase buyer confidence and the likely multiplier.

Local market strength, labor access, and site quality influence how buyers view future cash flow. Rural or weak markets often carry a discount.

Terms matter: seller financing, earnouts, and clear transition support can improve offers. Conversely, onerous working capital targets or short training windows can reduce the agreed multiple.

Improve fundamentals (clean books, durable revenue, lower risk) to earn a stronger multiple.

While SDE is a useful cash-flow shorthand, it omits real costs that affect a buyer after closing. Read this short list so you know what to check before using the number as a final guide.

Adding back depreciation and amortization restores accounting charges to cash, but it can mislead for equipment- or IP-heavy firms.

Buyers often model ongoing CapEx and maintenance costs separately because assets wear out or need replacement. Ignore that at your peril.

Growth, seasonality, inventory cycles, and receivables drive cash demands that normalized earnings do not capture.

A buyer may need significant working capital injections after closing even when reported earnings look strong.

SDE shows pre-tax owner income; it does not predict a buyer’s after-tax take-home pay.

Actual tax outcomes depend on entity type, deal structure, and personal tax situations. Factor taxes into cash planning.

Not every company should use the same earnings yardstick. The choice between SDE vs EBITDA depends on company size, how hands-on the owner is, and the buyer pool you expect. Owner-operated businesses typically rely on SDE to reflect true owner cash, while larger companies with professional management are better evaluated using EBITDA.

SDE suits small, owner-operated firms where personal pay and perks distort results. It helps buyers see true owner-level cash.

EBITDA fits larger firms with separate management and standardized reporting. Lenders and strategic buyers rely on it for clearer comparisons.

Both metrics adjust reported numbers with add-backs to highlight operating cash flow. Each helps compare opportunities and test deal financing.

SDE includes owner compensation and discretionary items, so it is less repeatable across sellers. EBITDA strips personal items and is more standardized, which usually eases diligence and supports stronger terms.

Practical takeaway: many sellers calculate both. The buyer type and company size usually decide which metric drives the final price and valuation discussions.

Small operational gains often translate into outsized increases in sale proceeds when a multiple is applied to owner-level earnings. Focus on durable improvements you can document across multiple reporting periods.

Prioritize price optimization, better close rates, and retention instead of risky expansion. Test modest price increases on a subset of customers and track lift.

Improve conversion with clearer proposals and measurable marketing campaigns that show ROI. Repeatable sales processes reduce buyer concern about volatility.

Cut costs that do not affect customer experience: renegotiate vendor contracts, right-size subscriptions, and tighten purchase approvals.

Avoid headcount or inventory cuts that harm service or trigger supply issues; those moves often get penalized during diligence.

Value roughly equals SDE × multiple. At a 3.5× multiple, an extra $50,000 in owner earnings can imply about $175,000 more in sale price.

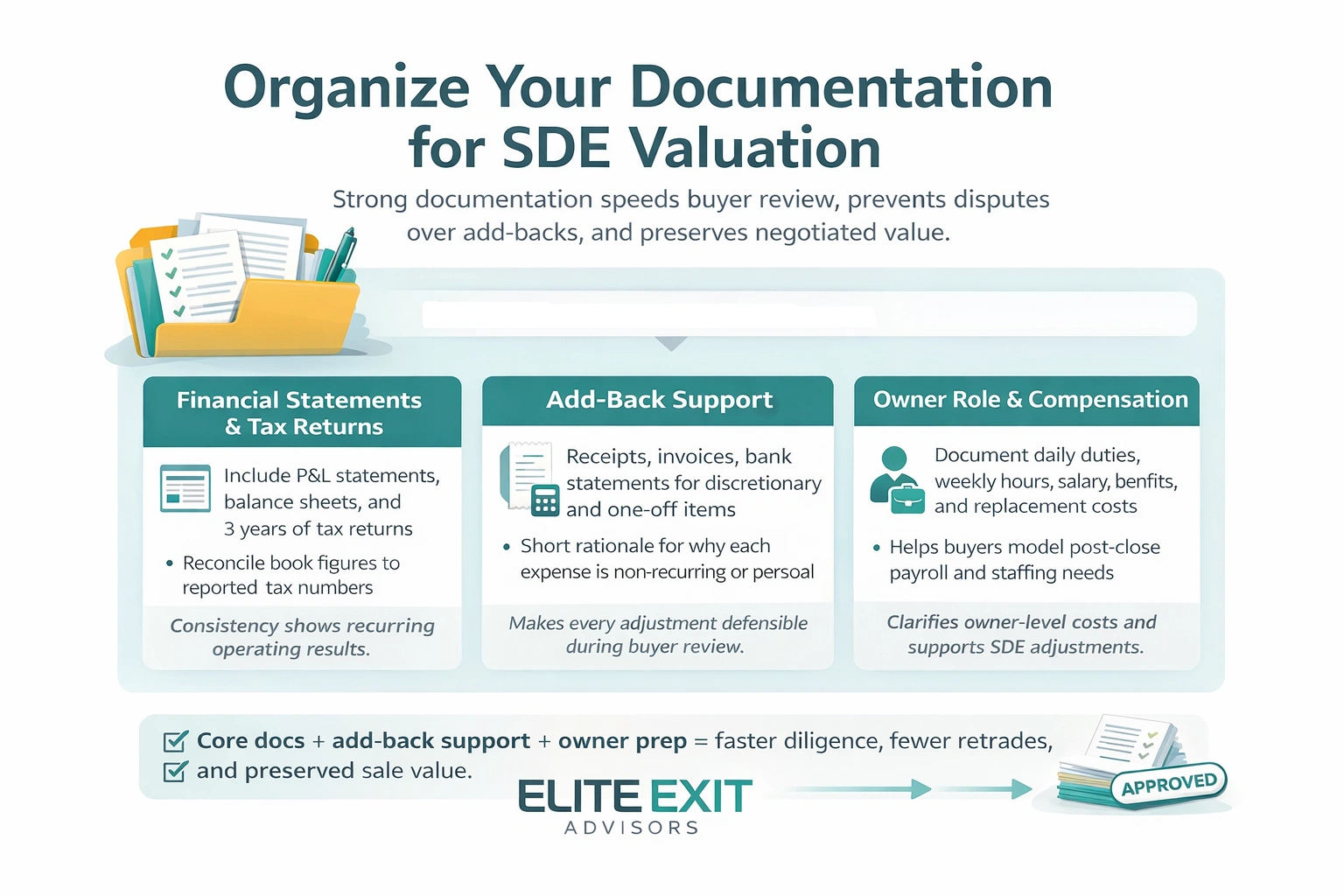

A well-organized file set speeds review and prevents last-minute disputes over add-backs. Start early and gather clear support for every adjustment you claim.

Provide profit-and-loss statements, balance sheets, and three years of tax returns. Include schedules that reconcile book figures to reported tax numbers.

Buyers spot inconsistencies quickly. Discrepancies slow review and invite discounting of reported owner cash.

For each discretionary expense or one-off item attach receipts, invoices, and bank or card records.

Add a one-line rationale explaining why the item is non-recurring or personal. This makes every add-back defensible during buyer review.

Document day-to-day duties, weekly hours, and a clear owner salary and benefits package. Show what a replacement manager would cost.

This helps a buyer model post-close payroll and staffing needs, and supports owner compensation adjustments claimed in the file.

Strong documentation helps sellers defend SDE numbers, reduces retrades, and preserves negotiated value when US buyers run diligence.

Getting the numbers right matters. Sellers who prepare a clear, documented earnings story face fewer surprises and often secure better offers from buyers. Elite Exit Advisors focuses on practical steps that make normalized cash understandable and verifiable for US buyers.

Practical deliverables:

We build concise narratives for each adjustment so a buyer can verify items quickly. That reduces the chance add-backs get stripped during diligence and keeps price talks on track.

Preparation lowers perceived risk. We identify value drivers, revenue quality, customer concentration, and repeatable processes, and show how fixing small gaps can lift multiple offers.

We do not inflate earnings. Our aim is to present normalized cash clearly so buyers can underwrite with confidence. If you want cleaner add-back narratives, fewer diligence issues, and a plan to improve business value before a sale, book a call to review current SDE, key add-backs, and an exit timeline aligned with US buyer expectations.

Treat normalized owner earnings as the practical bridge between accounting records and buyer expectations.

Seller discretionary earnings show true owner benefit and clarify post-sale cash flow. Start with earnings before taxes, add interest, depreciation, amortization, normalize owner pay, and include only defensible add-backs to avoid inflated figures.

Price often begins with SDE times a market multiple. That multiple reflects market demand, industry dynamics, and risk, so similar earnings can yield very different outcomes.

Use discretionary earnings wisely: forecast asset replacement, working capital needs, and taxes before treating the number as final. Clean records and clear owner-role notes reduce retrades and protect value.

Decide whether SDE, EBITDA, or both fit your sale based on company size, owner involvement, and the buyer pool.